Dr. Michael Lozman’s dream of a permanent Holocaust memorial in the Capital Region of New York became a reality on December 1, 2025, when Governor Kathy Hochul signed legislation establishing a New York State memorial to honor Holocaust victims and survivors.

“With the first ever state-sponsored Holocaust Memorial, we are honoring the victims and survivors of the Holocaust while ensuring that all visitors have a place to remember and reflect on what the Jewish community has endured,” Governor Hochul stated in a press release. “New York has zero tolerance for hate of any kind, and with this memorial, we reaffirm our commitment to rooting out antisemitism and ensuring a peaceful and thriving future for all.”

Legislation S5784/A7614 directs the state Office of General Services (OGS) to oversee the design, programming, and location on the Empire State Plaza in Albany of the New York Holocaust Memorial. The memorial will join others on the Plaza that are special sites of remembrance and tribute, offering visitors the opportunity to reflect on issues that touch the core of our society.

The late Dr. Michael Lozman was an area orthodontist and a passionate advocate for Holocaust remembrance. Lozman began his quest honoring victims of the Holocaust when he turned his attention to restoring desecrated Jewish cemeteries in Eastern Europe and, in doing so, educating future generations about the atrocities of the Holocaust. Working with several US colleges, Lozman organized and led fifteen trips through 2017 that resulted in the restoration of ten cemeteries in Belarus and five cemeteries in Lithuania.

Around 2017, Lozman began his pursuit of building a Holocaust memorial in the Capital District in New York. He had forged a friendship with Roman Catholic Diocese of Albany’s Bishop Edward B. Scharfenberger, who graciously donated two acres of land for the development of a memorial in Niskayuna. The gift from the diocese for a Holocaust project was the first known collaboration, for this type of memorial, between a Jewish community and the Roman Catholic Church. In 2018, Lozman founded the Capital District Jewish Holocaust Memorial (CDJHM). The board consisted of a group of individuals from the local community, including Scott Lewendon, Jean “Buzz” Rosenthal, Dr. Robin Lozman Anderson, Tobie Lozman Schlosstein, Warren Geisler, Gay Griffith, Howard Ginsburg, Judy Linden, and Linda Rozelle Shannon. “Michael was always grateful for each member’s sacrifice and sense of duty to the project,” recalled his wife Sharon.

Lozman’s initial concept for the physical memorial met resistance as being too literal a representation. Dan Dembling, an Albany architect, and Michael Blau, a theming solutions expert located in the Capital Region, were recruited to be part of the redesign effort that involved both the CDJHM and the Jewish Federation of Northeastern New York. Many iterations later, the Town of Niskayuna approved Dembling’s design in June 2019.

The planned memorial, as envisioned by the board, consists of walls arranged in the shape of the Star of David. Visitors will be guided around the six-sided structure, where they will be connected to significant events that occurred during the Holocaust. The six columns in the center represent the six million Jews murdered in the Holocaust. Initially estimated to cost $4.5 million, the board increased its fundraising efforts, but they were slowed down by the COVID-19 pandemic. In October 2023, Lozman decided to step back and leave the board. He asked Dembling, whom Lozman considered very capable and enthusiastic, to join the board and to become its president. After careful consideration, Dembling agreed. “Michael set the groundwork for me to think big,” said Dembling in an April 2025 Zoom call. “He was excited to transition the mission to me.”

Faced with new estimates due to inflation to $6 million, the board began exploring other locations that could provide already established restrooms and parking. Dembling proposed shifting the location from Niskayuna to the Empire State Plaza. It was felt that it would provide an ideal place for students and tourists who were visiting New York’s capital city an opportunity to learn about the Shoah. To further emphasize its expanded audience, the memorial will be renamed the New York State Holocaust Memorial (NYSHM). As the official state-sponsored Holocaust memorial, it is expected to draw contributions from the estimated 1.6 million Jews and other citizens of New York.

On October 11, 2024, one year to the day when he had called Dembling to take on the presidency, Lozman died. Continuing his work, the board sought letters of support from government, religious, and private entities. Armed with over forty letters, the board approached local legislators to establish the memorial at the Empire State Plaza. Senator Patricia Fahy and Assemblywoman Gabriella Romero drafted companion bills for their respective houses. Lozman’s vision moved closer to reality when both houses passed the bills unanimously. Governor Hochul’s signature moves the project to the NYS OGS, which must work with an “organization that provides Holocaust education services and programs” to deliver the memorial. The next step in creating the New York State Holocaust Memorial is up to the NYS OGS. The new law charges OGS with selecting an organization to work with on the memorial’s final design and location on the Empire State Plaza. The CDJHM hopes that it will be that organization.

Sharon Lozman, Dr. Robin Lozman Anderson, and other members of the CDJHM board were at the signing. Sharon received the newly signed bill from Governor Hochul as a lasting reminder of her husband’s legacy.

Along with the physical memorial, the board also added components that further incorporate Lozman’s vision of education. Under the guidance of Evelyn Loeb, a longtime Holocaust educator, the CDJHM partnered with Echoes & Reflections, an international Holocaust education program, to create an innovative educational program, which will include a historical timeline of Holocaust events and NYS Holocaust survivors’ testimonies. In addition, the CDJHM will sponsor a fleet of traveling memorials that use the same online educational program and will travel the state to schools, churches, synagogues, and other community locations. Both educational programs are scheduled to launch in the first quarter of 2026.

The Jewish Federation has been one of the many organizations that has supported the work of the CDJHM. At its annual meeting on June 17, the Federation honored three of its members. Dr. Michael Lozman was posthumously awarded the President’s Award; Buzz Rosenthal was also honored with a President’s Award; and Dan Dembling was awarded the Sidney Albert Community Service Award.

In a December 1, 2025, press release, Dembling thanked the governor for her signature. “Since our organization’s founding by Dr. Michael Lozman, we have been dedicated to creating a permanent space in the Capital Region to honor the victims of the Holocaust and educate future generations. At this time when antisemitism is so high and rhetoric is reminiscent of the Nazi era, the need to remember the Holocaust is critically important. As envisioned, this memorial will have statewide impact by helping to educate people about the consequences of prejudice left unchecked and hopefully inspire New Yorkers to stand up against hate in all its forms.”

“Michael planted the seed for all of this,” said Dembling. “His unwavering commitment to honoring the past ensures that the memories of those lost will continue to inspire and educate future generations.”

The Capital District Jewish Holocaust Memorial is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization and is raising funds for the permanent memorial, traveling memorials, and educational programming. Those wishing to donate or find more information can go to their website at https://www.cdjhm.org/ or email at info@cdjhm.org.

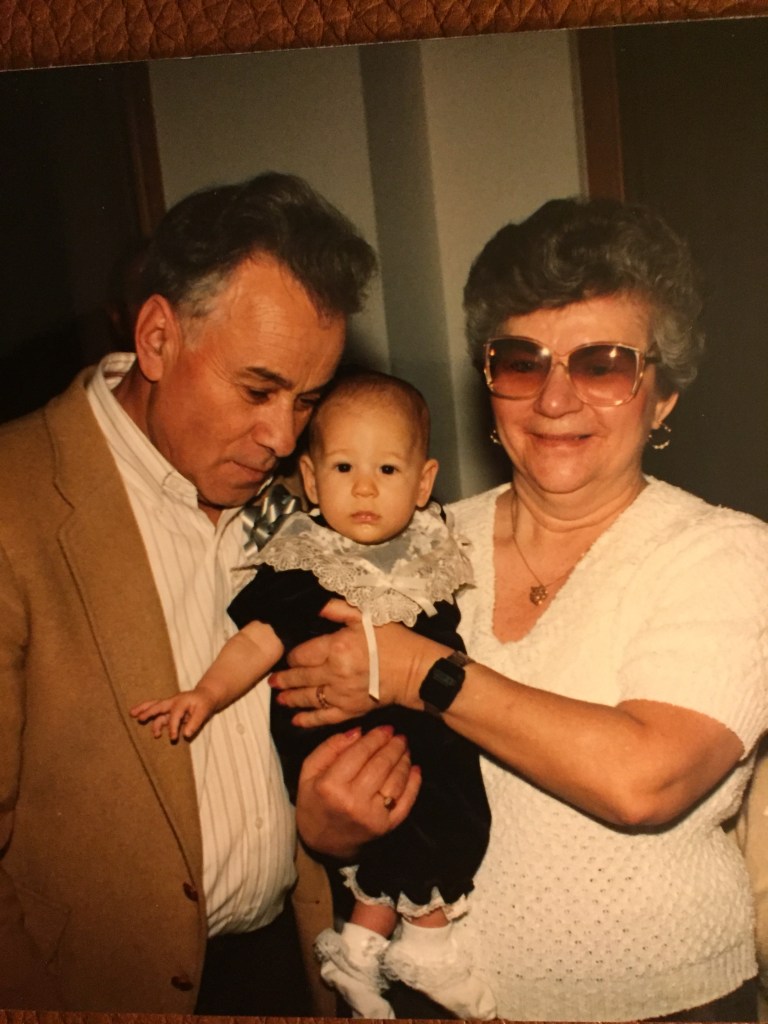

Dr. Michael Lozman

Photograph of CDJHC vision of Holocaust Memorial courtesy of Capital District Jewish Holocaust Committee, Inc. Dan Dembling, President.

Photograph of group at bill signing courtesy of the Press Office of New York State Governor Kathy Hochul. Darren McGee, photographer.

Photograph of Dr. Lozman courtesy of USCPAHA. Tina Khron, photographer. https://www.heritageabroad.gov/dvteam/dr-michael-lozman.