Ever since I could remember, my mother, Frances Cohen, was the family story teller. Give her an opening, and she would regal any audience with stories of her grandparents’ and parents’ lives in Russia, of her early years of marriage to “My Bill,” of their life in small towns and smaller apartments in the North Country, and of raising four children, watching them leave for college and for marriage, and their returning with her grandchildren to visit her and my father in their beloved cottage on Lake Champlain.

For many years, these stories were always told orally. Mom shared them when the family got together around the old oak table in the dining room, when she visited friends, and when her children’s friends came to visit. What was fascinating was that no one ever got tired of hearing them. As a matter of fact, she was highly regarded as the family historian. If anyone needed to know who was related to whom and how my father’s side was related to my mother’s side and what really happened between those two cousins—well, you just had to ask Fradyl, and the truth would be known.

As my parents got older, my mother realized that she needed to record these stories. We never were one for video cameras and tapes, so she began writing them down on lined paper, usually from the six by eight notepads. . The writing was messy, with words misspelled and whole sections crossed out, but she began to put them down on paper.

My parents retired in 1981 and spent the next nineteen years living six months in Florida and six months on a cottage on Lake Champlain. As it became too difficult to maintain two homes, they sold their cottage to my brother and sister-in-law, and my parents lived in Florida permanently. When I went to visit, my mother would tell me the stories as I transcribed them onto paper. Unfortunately, these scraps of paper remained in their original state for several years.

In 2007, after a number of health setbacks, we children insisted that my parents sell their condo in Florida and move back up North to be closer to the family. Everyone decided that the best location would be close to Larry and me, and on May 1, 2007, they moved into Coburg Village, an independent living facility only four miles from our home.

Initially uncertain about leaving Florida, their friends, and their independence, my parents soon realized that this was an ideal living arrangement that provided nightly five-course dinners in a lovely dining room, a shuttle service that brought them to grocery stores and doctor’s appointments, live entertainment and numerous clubs.

Soon after moving in, my mother called me to tell me she was joining Coburg’s monthly writing group to polish all those stories she carried in her head and on those scraps of paper. The night after her first meeting, however, she phoned to tell me she wasn’t sure she would fit in. “Most of them have college educations and write beautifully, Marilyn,” she lamented. “They will look down on my family stories as being silly and boring.” However, when she brought her first story to the group, her accounting of why she and my father moved to Coburg, she was surprised to find that the group enjoyed her writing style. “They loved my story, Marilyn! They said I have a real flair for story telling!” After that, my mother’s voice in phone calls after the monthly Wednesday meetings was filled with pride.

Mom rarely had difficulty finding a topic and writing it down with paper in pen. However, the group leader requested that the stories be typed so they could be published in the semi-annual collection and distributed to Coburg resident. My mother asked me, “my daughter the English major,” to type them, and, while I was at it, to do some proofing and minor revisions so that they would read more smoothly.

Thus began our five-year collaboration. Every month, about a week before the group met, my mother would give me her hand-written story, and I would bring over the typed version by Sunday afternoon. If I didn’t have it done by Sunday night, the phone calls would begin. “Marilyn, if you don’t have the time, just bring back my copy and I’ll read it from the original.” I would assure her that it would be delivered in time for her meeting, even resorting to sending the final copy to her via the Coburg fax machine.

The oral stories evolved into written documents, always original, always entertaining. She wrote about the Old Country: how her mother’s mother died in childbirth and how the two children were raised at first by an uncaring stepmother and then by a loving women who raised them and the seven others that followed; how my father’s father escaped from Russia in a cart filled with hay; what it was like living in Regalia and Vilna at the turn of the century with the fear of pogroms always on the Jewish population’s mind. She wrote about her mother’s family coming to America: how her Uncle Sam saved enough money to bring over his sister Ethel; how Aunt Lil turned down a job at the Triangle Shirt Factory a month before the fire because she thought it looked unsafe; how Grandpa Joe left his future bride at the jeweler’s as collateral until he got a second opinion of the diamond ring they were purchasing. And she wrote about our family: how she and Bill met on a blind date; how they raised four children in various small towns in the North Country, and, and how they came to buy their cottage on Lake Champlain. The stories were funny, sad, and painful, but they were always ready the first Wednesday of every month for her meeting.

When my father passed away in November, 2008, my mother’s contribution for December was an open letter to my father. She wrote that she was moving into a smaller apartment down the hall, but “Wherever I go, you also go in spirit.” Grieving quietly, she continued with her life at Coburg, going to the concerts, visiting with friends and family who were always stopping by to see her, and continuing with her writing. All of the children asked her to write about our birth and early childhood, but she always postponed those stories, focusing on the Old Country, her childhood, her Bill.

On December 22, 2010, my mother had a heart attack. The doctors recommended Hospice and living her remaining time to the fullest. She complied, enjoying visits from the children, grandchildren, her cousins, and the many friends she had made in Coburg and Clifton Park. She kept writing, and in February, with my sister Laura and I sitting close by, she shared her story: “The Birth of My First Child,” in which she described her joy in having a beautiful little girl and her fears that she would not be able to be a good mother. The last words, written in pencil on the bottom, were “To be continued……” She died four weeks later, one day before the March meeting.

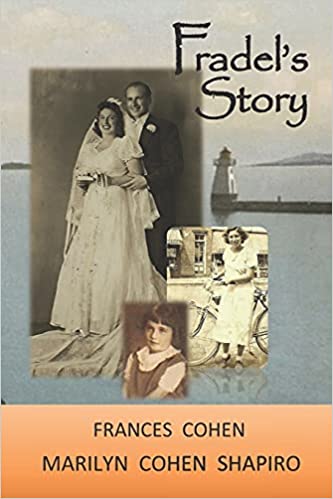

My parents were not wealthy people, and had little of material value: a wedding ring, two beautiful framed pictures of my father at thirteen and my mother at six, a few nice dishes. As my siblings and I sadly dismantled Mom’s apartment, my daughter was surprised that I wanted so little. “It’s ok, Julie,” I said, “We have her stories.”

And we do….Over one hundred typed pages as well as a file of her handwritten notes that she had kept over the years. What a gift to her family, her friends, and all who knew and loved this amazing woman!