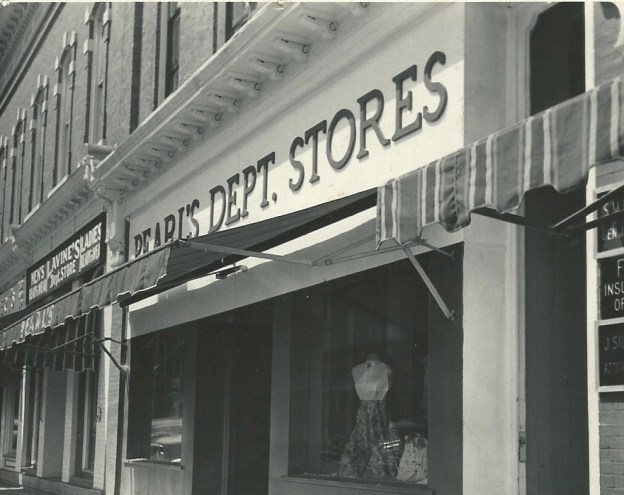

My father, Bill Cohen, (Z”L) loved to play Jewish geography, and he proudly shared with us how the first synagogue in Burlington was founded in his grandfather’s kitchen. As we lived on the New York side of Lake Champlain, we visited many aunts, uncles, and cousins who lived in the Queen City and the surrounding areas. One was Uncle Paul Pearl (born Pesach Ossovitz), who learned the peddling trade from his uncle Archic Perelman and went on to oversee 27 Pearl’s department stores in Upstate New York and Vermont. And then there were Uncle Moe Pearl, who owned several businesses in the area, and his wife Bess; Ruth (Pearl) Kropsky and her husband Isidore; and Aunt Ida and her husband Max Ahrens. May their memories be a blessing and live on in Congregation Ohavi Zedek and its beautiful “Lost Mural.”

When the Pels family attended the High Holy Day services in September, 2022, Congregation Ohavi Zedek had a welcome addition: the restored “Lost Mural” in the foyer, completed in June 2022 by the Lost Mural Project. The story of the mural began almost 150 years earlier, in the kitchen of one of its founding members, Isaac Perelman.

Although Jews had settled in Burlington as early as 1848, the 1880s saw an influx of Eastern European Jews facing persecution by Russians in all phases of their personal, professional, and religious lives. Others came up from New York City to escape work in the sweatshops; a few migrated from Plattsburgh, New York, as it didn’t have an orthodox shul. Most became peddlers in northern Vermont, selling their wares from horse or man-drawn carts.

Initially, a group of ten Jewish men—only two had families with them, met for services in members’ homes, a former coffin shop, or the second floor of an office building. By 1885, the Jewish community of Burlington, Vermont, recognized the need to organize a synagogue. Eighteen men met in the kitchen of Isaac Perelman, an immigrant from Čekiškė, Lithuania. Having already procured a lay leader/Kosher butcher, they purchased a lot for $25, formerly the site of an old stone shed at Hyde and Archibald streets. With $800, they built a synagogue building, naming their new shul Congregation Ohavi Zedek (Lovers of Justice).

Over the next few years, the Jewish population of Burlington continued to grow, fed by the founders. Isaac and his wife Sarah alone had six surviving children; his brothers Aaron and Jacob also had large families. By 1906, there were 162 Jewish families. The area in Burlington, dubbed “Little Jerusalem,” was laid out like the shtetls in the residents’ native Lithuania with houses and kosher bakery, kosher dairy, and a kosher butcher. The Jewish community built two more synagogues, including Chai Adam (Life of Man), and Ahavath Gerim (Love of Strangers). In 1910, the three synagogues built a Hebrew Free School together in 1910, the Talmud Torah.

In 1910, Chai Adam commissioned a 24-year-old Lithuanian immigrant and professional sign painter named Ben Zion Black to create a mural for $200. Upon completion, the project featured prayer walls and a painted ceiling. The centerpiece was a 25-foot-wide, 12-foot-high three part panel, created in the vibrant and colorful painted art style present in hundreds of Eastern European wooden synagogue interiors in the 18th and 19th centuries. The mural featured the Ten Commandments in its center and golden Lions of Judah on either side, with the artist’s rendering of the sun’s rays adding light. Blue and red curtains and pillars filled the side panels, all representing the artist’s interpretation of the Tent of the Tabernacle as described in the Book of Numbers and the Book of Exodus.

In 1939, amid a decline in the Jewish population, Chai Adam merged with Ohavi Zedek. After 1952, several buyers purchased the former Chai Adam building, which later became a carpet store and warehouse. In 1986, a developer purchased it with plans to renovate the building into multiple apartments. Recognizing that the future of the mural was in jeopardy, Aaron Goldberg, the archivist for Ohavi Zedek synagogue and a descendant of Ohavi Zedek’s founding immigrants, persuaded the new owner to seal the mural behind a false wall, in 1986. Goldberg, archivist Jeff Potash; Shelburne Museum’s curator of collections, Richard Kershner; and architect Marcel Beaudin hoped to reclaim the mural at a later date.

Before being hidden, Ben Zion Black’s daughters took and paid for archival quality photographs of the mural. Renovations destroyed much of the painting, but a wall covered the mural over the ark.

In 2010, Goldberg partnered with his childhood friend and former Trinity College of Vermont history professor Jeff Potash to establish the Lost Mural Project with plans to establish a new home for the mural and restore the work to its original glory. They reached an agreement with the Offenhartz family, the next owners of the Chai Adam building, that the mural would be uncovered and donated to the Lost Mural Project. This was done with the understanding that the Lost Mural Project would be solely responsible for all costs of stabilizing, moving, cleaning and restoring the Lost Mural.

In 2012, after over two decades, workers removed the false wall. A curator reported that Black’s creation had sustained extensive damage with “the painting hanging off its plaster base like cornflakes.” Over the next three years, the Lost Mural Project raised substantial funds from individuals, businesses, and foundations for the mural’s paint to be stabilized. In May 2015, workers moved the mural, encased in steel and weighing approximately 500 pounds, to Ohavi Zedek.

Following the mural’s move, the Lost Mural Project committee incorporated, rebranded and tirelessly sought funding for the mural’s cleaning and full restoration with the help of its board and Madeleine Kunin, the former Vermont governor and US ambassador to Switzerland. By 2022, they had raised over one million dollars from local, state, national, and international donors.

In 202, two conservators hired by the Lost Mural Project began the painstaking task of cleaning the mural. Using the archival photos taken in 1985, they used a gel solvent and cotton swabs to remove darkened varnish, dirt, and grime from the painting’s surface. The next year, a second team of conservators from Williamstown Art Conservation Center in Massachusetts began the infill, coloring and final restorations. According to Goldberg, the COVID-19 pandemic was a blessing, as it gave the team of workers the space and quiet needed to complete the project in the shuttered shul.

“So many things could have gone wrong with the mural, but it survived through fate and circumstance,” says Goldberg. “It’s not just a surviving remnant. It’s a surviving piece with an astonishing history.”

Ohavi Zedek’s Senior Rabbi Amy Small, who saw the 2022 restoration step by step, views the Lost Mural Project as a universal immigrant story. “It’s significant not only to the Jewish community and the descendants of those early settlers of Burlington, but also to other immigrants in the United States, which offered safety for Jewish and other families fleeing from many parts of the world.”

The Preservation Trust of Vermont presented the Friends of the Lost Mural with its 2022 Preservation Award. “The Lost Mural…not only exemplifies the rich history of creativity and resilience in Burlington’s Jewish community,” stated Ben Doyle, its president. “It inspires all of us to remember that the Vermont identity is dynamic and diverse.”

In June 2022, the completed project’s unveiling took place amid much fanfare. The Friends honored Governor Kunin for her contributions, and a Vermont Klezmer band provided the music. Dignitaries both in attendance and through Zoom highlighted the importance of the project. Joshua Perelman, Chief Curator & Director Of Exhibitions And Collections, National Museum Of American Jewish History called the mural “a treasure and also a significant work, both in American Jewish religious life and the world of art in this country.”

Many of the descendants of the original Lithuanian Jews who settled in Burlington over one hundred and fifty years earlier were present, including descendants of Isaac and Aaron Perelman.

“[The mural] tells us a remarkable story of a thriving Jewish immigrant community from Lithuania and the successful efforts of their descendants to preserve their cultural legacy today,” H. E. Audra Plepyte, the ambassador of Lithuania to the United States stated in remarks shared with Ohavi Zedek. “The Lost Mural is not lost anymore.

”The Lost Mural Project, an independent secular nonprofit, is seeking donations to replicate the green corridors on the original painting that did not survive. Its educational mission is to share the story of the Lost Mural and the lost genre of the East European wooden painted synagogues with people and facilities around the world.More information, including details of the Mural’s miraculous journey, can be found at https://www.lostmural.org/donate.

Originally published September 20, 2022. Updated May 26, 2025.

SOURCES

Thanks to Aaron Goldberg , Jay Cohen, Janet Leader, Rob Pels, and Rosie Pels for their contributions to this article.

Rathke, Lisa. “Long-hidden synagogue mural gets rehabbed.” August 17, 2022. AP Wire story; numerous sources.

Sproston, Betty. Burlington Free Press. February 22, 1995.

https://lostmural.squarespace.com/ekik-lithuania

https://www.news4jax.com/entertainment/2022/08/16/long-hidden-synagogue-mural-gets-rehabbed-relocated/

https://www.sevendaysvt.com/vermont/burlingtons-lost-mural-is-restored-to-its-original-glory/Content?oid=35853053

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/synagogue-mural-restoration-vermont-apartment-180980614/